credit: Justin Patchin Photography

by Angela Hugunin

We live in a noisy world. Threats of illness and uncertainty loom ahead, especially in the midst of the coronavirus outbreak. Distractions threaten to pull us away from what matters most, and what happens outside threatens to drown out what we experience beneath the surface. As writers, we’re sometimes left wondering how to make sense of all the chaos around us.

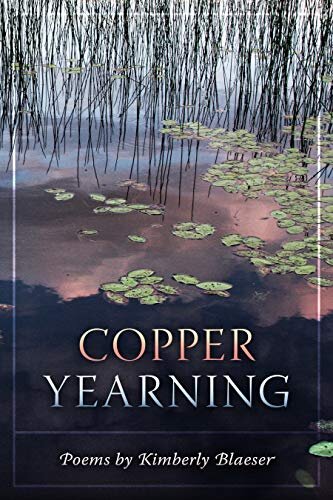

Kimberly Blaeser is aware of these distractions, yet as a poet, she regularly probes what lies beyond in search of what is deeper and more true. She has a breadth of experience in this realm; she has published four books of poetry: Trailing You, which won the first book award from the Native Writers’ Circle of the Americas, Absentee Indians and Other Poems, Apprenticed to Justice, and most recently, Copper Yearning. In addition to her writing, Kimberly is a professor at the University of Wisconsin—Milwaukee. She served as Wisconsin Poet Laureate from 2015-2016. Of Anishinaabe ancestry, Kimberly is an enrolled member of the Minnesota Chippewa Tribe. She grew up on the White Earth Reservation in northwestern Minnesota and worked as a journalist before earning her M.A. and Ph.D. from the University of Notre Dame.

I had the honor of speaking with Kimberly, this year’s poet-in-residence for The Priory Writers’ Retreat, which will take place from June 25-28. Applications are now open for Kimberly’s workshop, “Poetry of Spirit and Witness.”

Angela Hugunin: You recently released a moving book of poems, Copper Yearning. I’ve taken a long time to finish just because I’ve wanted to savor each and every poem! In the book, you explore individual and collective memory, as well as the experiences that linger with us. What is our responsibility as witnesses and writers?

Kimberly Blaeser: In a world filled with surface, with distractions, we must learn to look past all that “noise.” I understand poetry as an “act of attention.” We cannot embody our world in writing, unless we first see clearly—witness fully. I believe part of that “seeing” involves recognizing the intricate relationships at work in the world, replacing the static picture postcards—the surface—with a deeper vision.

On a practical level, as writers we touch the tangible with our language—the jagged edges of broken glass, broken lives; spring kilting into blossom; whispered night litanies just now as coronavirus raises fears. To make experience intelligible, we first pull our readers into it imaginatively. Our responsibility cannot be mere reporting or analysis. Some readers may believe us, but they won’t truly understand our subject unless we allow them to “experience experience.” We must pass them sticky, bruised, solemn, turquoise reality—the truth braided into complexity.

AH: One of my favorite elements of Copper Yearning is the way you illustrate beautiful yet sometimes broken connections between people and place, humans and animals, and history and future. These subjects aren’t always easy to make tangible. How do you ground some of these profound subjects in your writing?

KB: I coax myself to allow the subjects their messiness. The relationships between humans and animals, for example, involves the alpha longings and complexities of interspecies belonging. Humans are animals. They have survived partly because of their animal instincts. Yet, humans fear their own “animal nature”—and they fear losing it. We tell ourselves origin myths that link us with nonhuman creatures, write popular fictions about beings half human/half wolf, and value our “kinship” with wild creatures. Yet we have hunted species to their extinction. These statements barely begin to trace the complexity of the human/animal relationship. If we remember no relationship has a simple through line, our tracing of the interconnections can then invoke both the beautiful and the broken in the same piece. This intermingling will inch toward a truth our readers may find more memorable than an easy, straightforward representation.

AH: I had the pleasure of hearing you speak and share some of your work at a Chippewa Valley Writers Guild event last fall. Hearing words you’ve written from you in the flesh brought them to life for me and left me covered in goosebumps. For the Priory Writers’ Retreat, participants have the benefit of being there in person. What can in-person connection bring to writing?

KB: In a random conversation with someone I met last week, we discovered we had both been present at Woodland Pattern book center for a particular spell-binding performance by a Japanese poet. When my son was in utero, he began “dancing” at a Joy Harjo performance. Poetry is by its nature musical; nothing can replace hearing it performed aloud. Priory writers will have the chance to experience both the song of poetry and dramatic prose performances.

But creating in a community setting has other advantages as well. You have the time already set aside for writing intensively (living and sleeping with your writing, writing and revising and not cooking!) You will have the pleasure of exchanges with other people who value the power and beauty of language, who understand your preoccupations with image, the “right” word, allusion, even punctuation. Writers benefit from workshops on particular aspects of writing, and from discussions about individual works—your own and others. Instructors or other workshop members may model for you some aspect of the craft, inspire you to return to your own work with more vigor, or pull the veil back on some of the “business” aspects of writing and publishing.

AH: Your workshop for this retreat is titled “Poetry of Spirit and Witness.” For you, how are spirit and witness connected?

KB: Witness, the way I think of it, is both to see and to speak or “bear witness.” The word "spirit" likewise brings together various ideas—everything from the soul to a notion of vigor. For me, the two terms come together in a kind of poetry that speaks truth, that hearkens after understanding or enlightenment. Carolyn Forché talks about “poetry of witness” as a poetry “invested in the social.” Perhaps in my own practice the lens through which I refract experience involves justice. The process includes vision and the Latin spiritus as in breath to speak. But I also bring to it the sense of [being] inspired or soul and, therefore, a stance of an ethical and searching accounting.

That sounds very hoity-toity. On the most simple level, for me poetry of spirit and witness arise out of experiences that resonate and “mean” in a way beyond the ordinary moments. Oddly, that does not suggest they might not actually arise out of ordinary moments—an encounter with a pine marten, hearing a fiddle song, etc.. These poems might take as subject anything from war to lighting a cigarette, but what sets them apart is the significance embedded in the experience and the revealing of that deep understanding through the narrative details, language play, metaphors, and other tools of the poem.

AH: We’re approaching the application deadline for this retreat, and energy is already building! What are you most excited to share at the coming retreat? What are you hoping to see?

KB: Sometimes we need to be led to break open our own experiences. I use various exercises that help writers recognize and unearth the richness of their life encounters. I like to spend the time in a writing retreat to allow participants to create drafts of new work there on the spot, but also in helping them create a “bank” from which they can draw once they leave the workshop. I also try in various ways to harness the energy of working with other writers by creating scenarios that encourage cross-pollination.

Among the things I hope for: Writers getting nitty-gritty feedback AND getting wilder “what-if” feedback that might push their work out of their comfort zone. Writers making connections that will continue beyond the retreat itself.

AH: I know many of us readers are always eager to gather more books to read in the future (or right now!). We’re down to a few months before the retreat, so now is a perfect time for some of us to keep stretching ourselves in reading and writing. What have you enjoyed reading lately?

KB: I recently finished Carolyn Forché’s memoir What You Have Heard Is True, an amazingly powerful story of her experience in El Salvador, a book both lyrical and brutal. I followed that with the novel The Tilted World co-written by Tom Franklin and Beth Ann Fennelly. Against the backdrop of the great Mississippi flood of 1927 and prohibition, the novel tells a story of relationships that kept me reading way past my bedtime! Now I am embarking on reading Natalie Diaz’s Postcolonial Love Poem—can’t go wrong there.

“Unlawful Assembly,” a picto-poem from Kim

AH: What makes this retreat a must-attend for writers, even those who aren’t sure they’re “qualified” to write poetry? What would you say to writers who are on the fence about applying?

KB: I would say, “Be fearless, come write with me!” Or I would say there are as many ways of writing poetry as there are poets. We, none of us, ever feel “arrived” as poets. I do think we learn to have more fun as we go along, so there is no better time to jump into the fun than right now. If you have a moment or several that are asking to be written about, if you have witnessed something that changed you, if you can’t find a way to say that unsayable thing that haunts you, this might be the workshop for you.

Join Kimberly Blaeser, Nickolas Butler, Tessa Fontaine, and Peter Geye at this year’s Priory Writers’ Retreat, from June 25-28 in Eau Claire. Click here for more information about the workshops and here to apply. We look forward to writing with you this summer!

Want a few more resources? Click here to hear Kim read, here for a new poem in collaboration wth the New York Philharmonic,