When driving around Eau Claire, the attentive observer may notice the aging architectural remnants of a once-emerging industrial city: an abandoned sanatorium, a funeral home along the Chippewa River, a historic “cottage style” gas station. Over the years, a few such structures have been updated to fit with the rest of the modern-day scenery, though much of the history of these buildings (and those no longer standing) is preserved by way of photographs archived at the Chippewa Valley Museum.

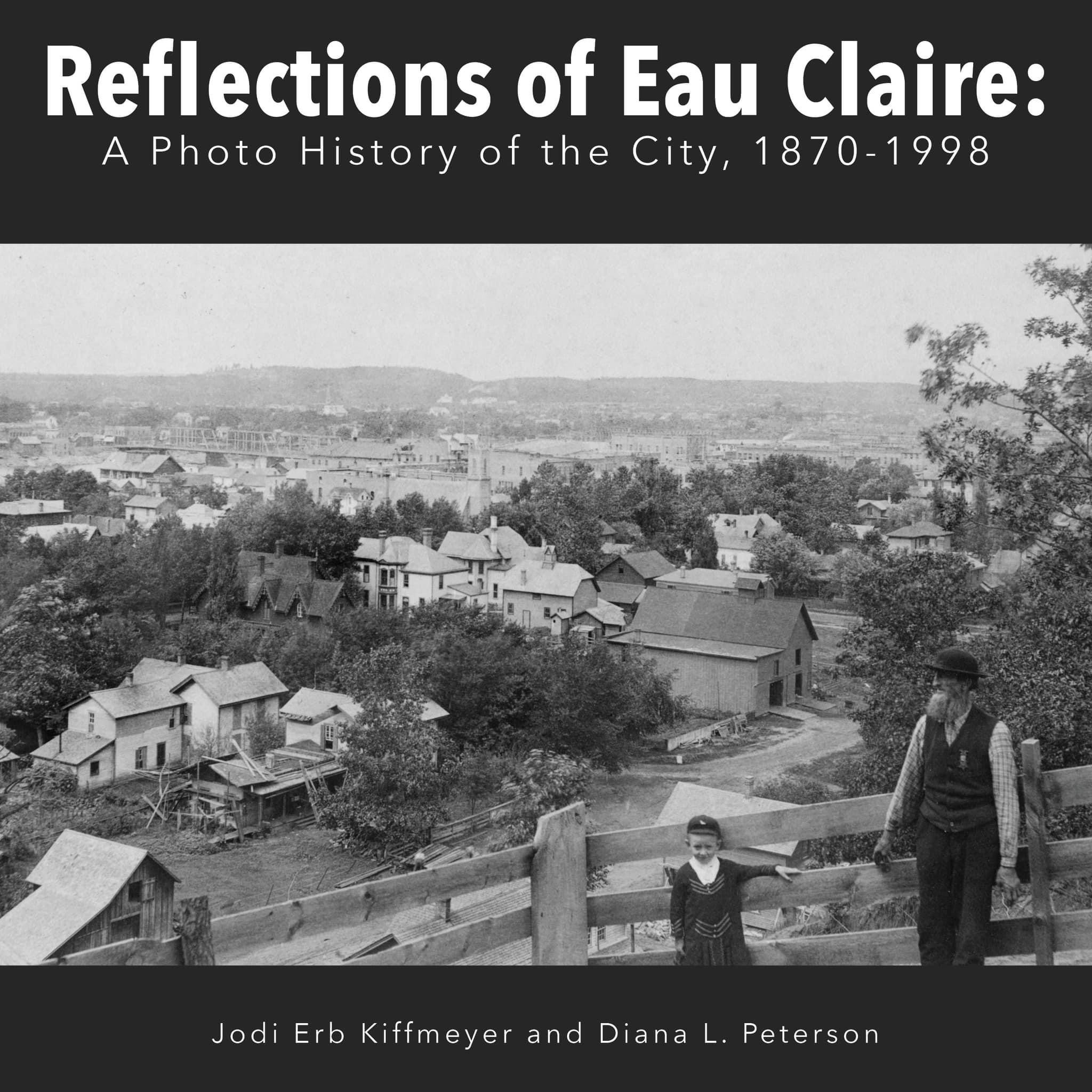

Jodi Kiffmeyer and Diana Peterson work at the Chippewa Valley Museum as the archivist and editor/assistant curator, respectively. Together, they collaborated to research and write a book using a small fraction of the 27,000 photos in the museum’s collection. Reflections of Eau Claire: A Photo History of the City, 1870-1998, is the product of extensive research that combines historical photographs with short descriptions of related events and people.

““Jodi and I work really well together because we like very different eras...So, Jodi’s really into the 1880s through the 1920s, and I’m more into the 1930s through the 1960s.” ”

“Jodi and I work really well together because we like very different eras,” Peterson says. “So, Jodi’s really into the 1880s through the 1920s, and I’m more into the 1930s through the 1960s.” Their passion can be seen on every page of the book, from Eau Claire’s beginnings as a lumber town to the development of industry and downtown entertainment. Iconic landmarks like The Joynt and the Hollywood Theatre are included in its pages, along with surprising historical facts. “If you’ve only been here the last ten years, you have absolutely no idea of the history of [The Joynt] regarding guests and the unbelievable jazz musicians that came to Eau Claire and performed here,” Peterson says.

In addition to the included photographs, Kiffmeyer and Peterson found other sources to help tell the stories of iconic buildings. One of the more interesting sources is Ralph Owen, an Eau Claire resident in the first half of the 1900s. “Ralph Owen was a guy who grew up in Eau Claire, and he had copious notes of what went on in Eau Claire, [including] a couple thousand pages of a manuscript that were donated to the archives,” Kiffmeyer says. “That’s where I get a lot of information.” Even the city directories lack a lot of the information that residents like Owen have otherwise documented.

Many of these buildings included in the book can no longer be found standing in Eau Claire. However, their stories are preserved in other ways, often through the work of volunteers or people passionate about preservation. “[In] a lot of ways this book is the story of success, and what you might call failure of people trying to preserve the history of Eau Claire,” Kiffmeyer says. The Soo Depot, destroyed in 1997, was an important stop for train routes through Eau Claire but no longer had a use as demand for public transportation waned. Its legacy is now preserved through photos and records kept by the history museum even though the building is no longer standing. The Depot occupied the S Dewey and Eau Claire streets, near the L.E. Phillips Public Library.

Despite having so many sources of information to draw from, much of the information had to be left out to present the photos effectively. “For a lot of these [photos] I could have written three or four times as much as I did,” Kiffmeyer says. “This is just scratching the surface of some of these stories.” Kiffmeyer and Peterson view this as a great opportunity for those interested in local history to support the Chippewa Valley Museum since a membership allows access to the entirety of its archive for Eau Claire and further information on each picture in the book.

Reflections of Eau Claire: A Photo History of the City, 1870-1998, is available for purchase through the Chippewa Valley Museum’s website, and members can get an additional 10% off through the Museum store. Take some time to reflect on the rich history of Eau Claire by picking up a copy today.