EM: That's a great point because, I mean, a business is looking at their bottom line. But of course you as a writer, the artist, you're looking out for your vision. So there's a kind of collaboration that has to occur, and you do have the same goal in mind to sell the book.

TW: There is a way to have balance. If you have industry people who are not hearing you, then it's your job to go figure out how to get them to hear you, how to speak their language. I think throwing tantrums or not saying what you feel is not helpful. You have to advocate for yourself. I've never had a job where I didn't negotiate my salary, even when I was working at a restaurant because I know my worth. And I knew it's also my employer’s job to pay me as little as they can because they have a budget that has to stretch very far or whatever. I took those skills from my regular life and used them in publishing. Like, "What is the goal we're trying to accomplish here and how do I get you to hear me?"

EM: Ooh, so you said that when you’re in your lane, you shouldn't be thinking about all the things that will happen until after you start working with the publisher. But at what point do you really get a sense that your time in your lane is coming to an end and it's time to start merging?

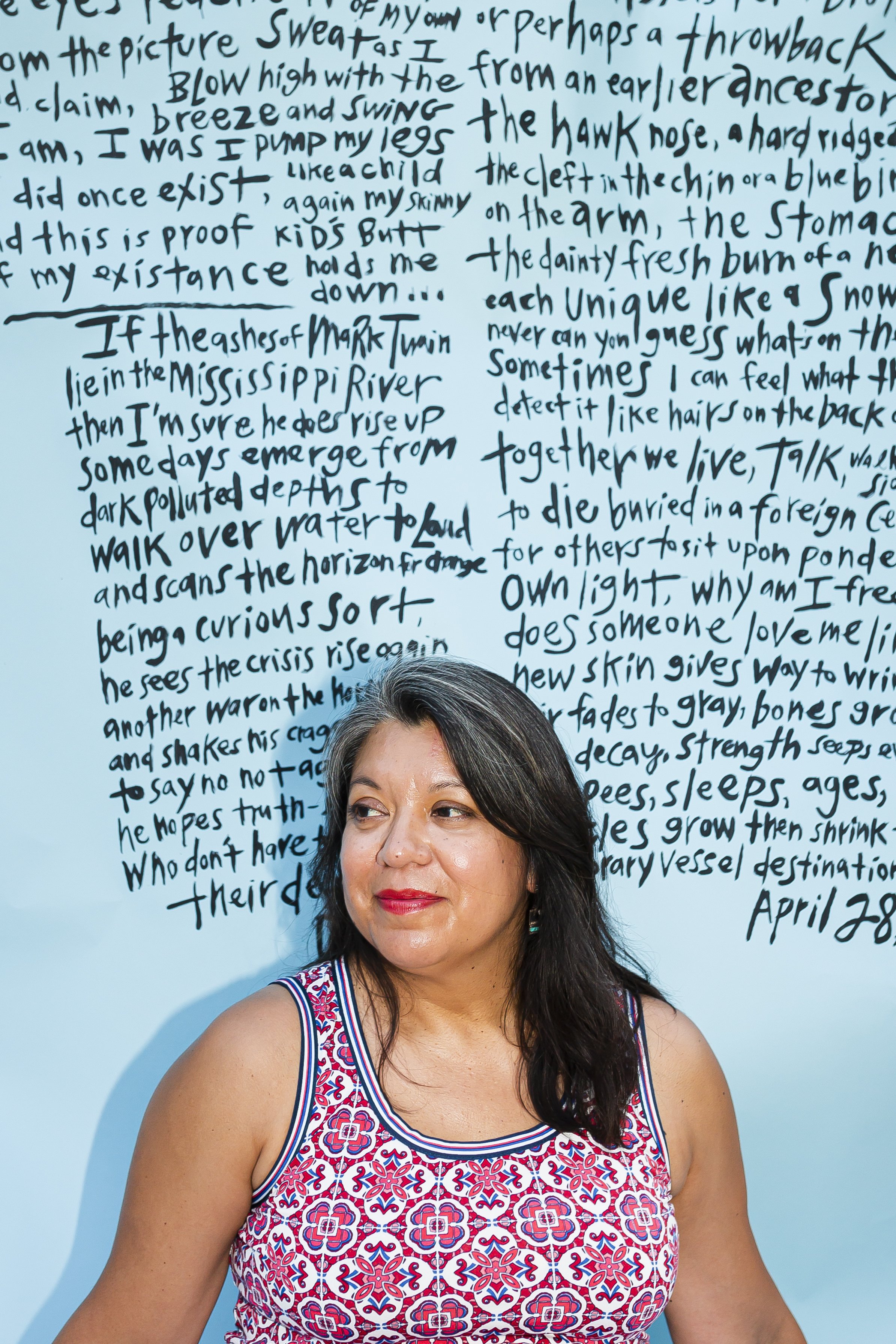

TW: I think once you've sold the book. Once you get industry people involved, it's time to think like them. But I think the problem is when it's just you and your computer or your story, we've got other people in the conversation who don't belong there. I have a friend who recently decided that she's going to write a story, and one of the things I'm going to drill into her head is that only you and this story exists right now. Do not share pages with no body. Okay? You don't think about who's gonna publish it. You're in a season where it's just you. You know what, I'm gonna quote CV Peterson. CV is a visual artist, right? And the two of us, our worlds of art cannot be further apart. I'm a writer. She's a painter, sculptor. Like, she's a visual artist. We get together and we talk process in a very pulled back way so that we can encourage each other and kind of have art therapy. We really are art therapy for one another. And I have been on a tour longer than I thought I would be. I was having a lot of conversations, speaking engagements, just ripping and running all over the place at a time when I thought I'd be working on my next book. January, February is always the time when I start a new thing. It's cold and stupid outside. I got my cup of cocoa, I'm writing down and looking at the snow–it's great. This year, I was traveling, I was speaking, I was exhausting myself. So I'm up visiting CV in Eau Claire, we're chatting and she's like, “Toya, the problem is you're not acknowledging that you're still in "showing season," and you're trying to go to "making season" when you're not in "making season."” She has "showing season," "making season," and "research season"–that's kind of the chunks of her artistic life. We call it book promotion or the tour or whatever, but essentially, I have been in "showing season" longer than I ever thought. And it's a privilege and it's an honor. And I have to just fall back and acknowledge that I'm not in a season where things are still and quiet and it's just me, and I can start writing my next book. People want to ask you, “What's next? What are you working on?” And no one wants to hear you say, “I'm working on telling more people about this book,” but it's real. I was in the UK because the book came out on March 23rd. I was able to go to a string of bookstores in London, and I was able to sit on a panel about girlhood. And the other folks on the panel were from London, they were from Jamaica, they were in their 60s, I'm in my 40s, and the other girl’s probably in her late 20s, if I had to guess. So whatever season you're in, you have to stay in it and honor that. Man, I forgot your original question. Why did I go off on this tangent?

EM: The question was–oh my gosh, I was just so swept up. Oh yeah! When do you know that it's time to come out of your lane?

TW: Yeah, so right now I am still technically in the publishing lane. All up in it. I have an independent publicist. I have a publicist at my American publisher, HarperCollins. I have a publicist at Penguin UK. I spend most of my time talking to publicists because we are still promoting all the versions of Last Summer on State Street. The paperback version is going to be out. So I'm still in the publishing lane right now, and I am hoping that this summer I get to come out of their world and back into my very small, quiet space, where I'm just creating and throwing a mess on the wall and being like, “Oh, I like how that's dripping!” I'm so excited because that's the stuff I love. But it's also a privilege to have a book–to still be in conversation. The book was published on June 14 of last year, and people still want to talk about it, people are still finding it. And I think for people who are writing a book there is this temptation to think about who's going to buy it. What publisher, who's the audience–all those things. But you're gonna have people whose specific job is to think about that stuff. They can't write the book–you have to write the book, you know. So that is your first lane, first and foremost. And if you decide to change lanes for a time because it's necessary, don't forget that you're gonna go back into the lane of writer. And then again, you've got to box out and keep everybody out until it's time to have to let them come over into your lane.

EM: I love that interweaving answer! But, okay, you are probably one of the most outgoing and friendly creatives–particularly a writer–that I've ever met. Being in your lane, writing your book, your story–that's just you and the chair, interacting with the page or the screen. But eventually, your creative community is going to be a part of that. You've been in the game for over 20 years. What's been your journey building a creative community? And how does your community sustain and influence your work, especially since you have an ever-expanding circle of friends? I feel like I could look away for five minutes and you've made 10 new friends.

TW: You know what it is? I think you have to hold on to people. When I studied creative writing as an undergrad, I went to a school called Columbia College Chicago, and it was one of the only schools in the country that had a bachelor's degree in fiction writing. I always knew that this program existed, but it was in Chicago and I was trying to flee Chicago. I wanted to get out of the housing projects and get as far away from Chicago as possible. I failed, but it was a good thing. So I always knew that Columbia had an actual fiction writing major, and I was so fascinated by that. I would be in workshops, and I would always pay attention to who got excited. Because in our program you had to actually write in your notebook in class, and then you would read a little bit of it back. So over the course of 16 weeks you really get to know somebody’s work really well. You're like, “Oh, we're back to that same monster.” You will look up and see whose eyes are twinkling when you're reading your stuff. And those are the people you want to stay in touch with because they get what you're trying to do and are excited about it. I learned early on that you need to grab a few writers who are going to make up your sort of writing community. Maybe you'll be in a workshop with them, or maybe sometimes you'll talk process with them on a break. You'd be sharing, “Yeah, I'm really struggling with this character. I just don't like them.” And I think I learned in childhood about friendship–when you connect with people, you should keep them. I think when I started studying writing, it became that you need to figure out which writers you want to hold on to. I have a mentor friend who jokes that my life is full of these concentric circles of friends and community, and it's because I don't let good people go. Whether they are creatives or just folks who have a similar faith tradition. It’s just the practice of holding on to good people that I learned a long time ago, and I sort of apply it to my creative life as well.

EM: That's a powerful way of being. That's not just art-sustaining, that's life-sustaining.

TW: Yeah, yeah. I think now that I have a book out, there are people who genuinely are cheering me on because they know I showed up for them but also know this is a big deal. I've been working on it for a long, long time, and they're all “Look at you go!” and they're informed cheerleaders. They're not just here for the magic of it all. They're saying, “Man, this woman–she held onto this book forever!” I mean, I have friends who had a book they worked on for a while and they set it aside and started a new thing. But for some reason, I just decided to keep hammering away at this thing obsessively. So, people know my story. They know this. I started a long time ago, and a lot of them have read drafts, they've given me notes. A lot of them are on my acknowledgments page because it's been such a journey. I've kept some of the same people, but along the way I picked up some new folks too.

EM: I remember the first time I read any of your words, I had never met you in person. In fact, I don't think I met you until months after. I was staying at Envisage Retreat for one weekend, and when I walked in, I saw the “They landmarks” quote and asked, “Who wrote that?” because I thought it was so powerful. And CV said, “Oh, that's from my friend Toya. She's from Chicago. She's working on this manuscript,” and I knew I had to read it. From then to now, it's been so incredible to see you come along and blow up!

TW: And Eau Claire and Chippewa Falls–these towns have been such an important part of the creation of this book. Because since 2018, I've been coming up just to work on it in the winter. It's sort of full circle.

Join Toya Wolfe for a reading and conversation Thursday, May 4 at 6:30 PM at the L.E. Phillips Memorial Public Library.