credit: RT Vrieze of Knorth Studios

Elizabeth de Cleyre

In the fall of 2022, Matthew Mabis casually mentioned to friends at a bar about how he’d started writing letters to the head coach of the Green Bay Packers. The conversation moved onto something else, and later, Mabis joined his friends onstage to play a set. After the show, the band loaded all of their gear into one car for someone to bring home and unload, and the rest of them loaded into another vehicle. Mabis, alongside his friends and band mates Matt Vold, Dan Turner, and Jack Gribble, left downtown Eau Claire after midnight and headed east. They stopped in Wausau, hanging out at a bar and crashing at a motel for a few hours. Then they got up the next morning and drove to Lambeau, with enough time to tailgate before the game.

Although I’d lived in Wisconsin for six years at that point, this was a different level of fandom than anything I’d ever encountered.

You see, I grew up in a place called ‘Patriots Nation.’ My home state doesn’t possess its own NFL team, and defaults to cheering for its regional representatives. I went to high school during the heyday of the Tom Brady–Bill Belichick era, but never liked the Patriots, or Brady, or their fans. I could not comprehend why anyone felt so invested in the success of a for-profit team belonging to one wealthy white dude.

The citizens of early 2000s Patriots Nation hated a lot of teams, but there was a special animosity reserved for the Green Bay Packers. In 1997, the Packers defeated the Patriots 35-21 to earn their third Super Bowl victory. A guy from my hometown once told me he remembered that game vividly, even though he was only nine. It was the first time he could recall watching the Super Bowl with his father, and when the game ended, his father's disappointment at the loss was so palpable that this nine-year-old boy vowed to hate the Packers for all eternity.

My own introduction to Packers fandom came ten months after moving to Wisconsin, when I was asked to help coordinate a book fair during the town's annual literary festival. The organizers scheduled it for a Sunday in October at noon and I was unaware the Packers were also scheduled to play that Sunday in October at noon. It would be the team's first matchup in four years without quarterback Aaron Rodgers, who was out with a broken collarbone. But, I thought, surely the audiences for a literary festival and NFL game would not overlap. Surely the bookish types didn't clear their Sunday schedules to watch the Packers.

Never have I ever been more naive, or more wrong.

That day, more than anything before or after, proved I was in a strange new land — one where the football fans and literary circles converged. Tables were set up in The Local Store and Oxbow Hotel's gallery for author signings and booksellers, and the initial burst of activity subsided when the game began. One author sat behind a table with nary a trickle of readers seeking signed books — unusual, in this town. Before he left, he came up to say goodbye, and added how it's hard to compete with a Packer game. He said it kindly, even humbly, perhaps even pitying me — a newcomer to this land — for so blatantly misunderstanding its culture.

In a 2023 article for The Guardian, journalist Katie Thornton explains the ownership structure of the Green Bay Packers:

“Instead of a sole wealthy owner who won’t hesitate to leave if the city doesn’t pay up, the Packers are owned by more than 500,000 community shareholders - none of whom can own more than about 4% of the team’s stock. Unlike shareholders of other corporations, Packers owners can’t sell or cash in their shares. And unlike other teams, which generate windfall profits for the team owners, all Packers profits are invested back into the organization. Often these funds go toward stadium updates, giving the team a sort of opt-in public funding model that has repeatedly paid for the Packers’ community-oriented projects - even if they aren’t likely to yield a huge financial return. This structure has enabled the team and city to build a football mecca that, were it left solely to the high-rolling sports market, would have no business surviving in a small city like Green Bay, which has a population only a little over 100,000.”

“Once I realized the Green Bay Packers are the only publicly-owned major professional sports franchise in the United States, the fervor made sense. Here was a fanbase with a literal and figurative investment in the team.”

Once I realized the Green Bay Packers are the only publicly-owned major professional sports franchise in the United States, the fervor made sense. Here was a fanbase with a literal and figurative investment in the team.

To mention the Packers is to conjure up stories of parents who put the names of their one-day-old babies on the waitlist for season tickets. These babies become adults and gain access to their seats at Lambeau in their mid-thirties, just in time for them to start a family and add their baby’s name. Rather than passing down a lucky jersey, a signed football, or a piece of memorabilia, fans passed down season tickets and shareholder stocks, lending more weight to the intergenerational aspect of fandom. We may not always gravitate toward or fall in love with the teams our parents rooted for, just like we may not become committed to our ancestors’ religious denominations. But in Wisconsin, life revolves around the Packers: births, first communions, marriages, and deaths can be ushered in, celebrated, or mourned by the transfer of owner shares or the promise of season tickets.

Even though the book is titled Against Football, the author Steve Almond writes of his love for the sport, and how he believes, “football, in its exalted moments, is not just a sport but a lovely and intricate form of art.” Recounting the history of the game, he says, “football provided a lingua franca by which men of vastly different beliefs and standing could speak to one another in an increasingly fragmented culture.”

We witness it here in Wisconsin, where the literary circles and sports fanatics overlap. Almond points out author Don Delillo’s “exquisite renderings” of the game in his novel End Zone, which he says hinted at the idea “that sport awakens within us deep recesses of emotion, occasions for reflection, reasons to believe.”

Yet the bulk of Almond’s book tackles (pun intended) the issues with the game’s violence, which can cause long-standing health issues for players, most notably in the form of traumatic brain injuries and chronic traumatic encephalopathy. When he visits Ann McKee, M.D., a neurologist in Boston studying football-induced concussions, Almond points out the Aaron Rodgers bobblehead among her items and how she calls the team “her Green Bay Packers,” a fitting use of a possessive adjective for a team owned by the fans.

Even though McKee’s research proves the seriousness of these injuries, there’s doubt the evidence will change the NFL. Instead, the author writes, “The ultimate agents of social change aren’t researchers like her, but individual fans (like her) who confront the moral meaning of the research.”

One might even go so far as to argue the agents of social change could come specifically from the Packers fanbase, the only team with a vested interest in listening to their supporters.

The author, Matthew Mabis, as a young fan (right).

Credit: Ann Mabis.

Matthew Mabis is one of those fans. If you happen to catch the English teacher watching the game at a local haunt, you might be lucky enough to hear some of his cogent commentary. While other fans are yelling and swearing at the television, Mabis is calm and measured. After the completion of a pass or touchdown, you’ll hear a slow clap from his side of the bar, perhaps paired with an encouraging yet understated affirmation. When the cheering dies down, you might hear Mabis chime in with a detailed play recall.

One of his previous apartments contained a shrine of team memorabilia set up on an old radiator. Before games, he and a friend would make bloody mary’s and read from Jerry Kramer’s Instant Replay, the former Packer’s diary of the 1967 season. It would be head coach Vince Lombardi’s last year coaching the team, which won the Super Bowl against the Oakland Raiders. During these weekly meetings of Packer Church, Matt Vold would open up to the corresponding date of that day’s game and read aloud from a passage.

“When Mabis started this project, he had no intention of publishing the letters. He only wanted to reach one person: Head Coach Matthew Patrick LaFleur.”

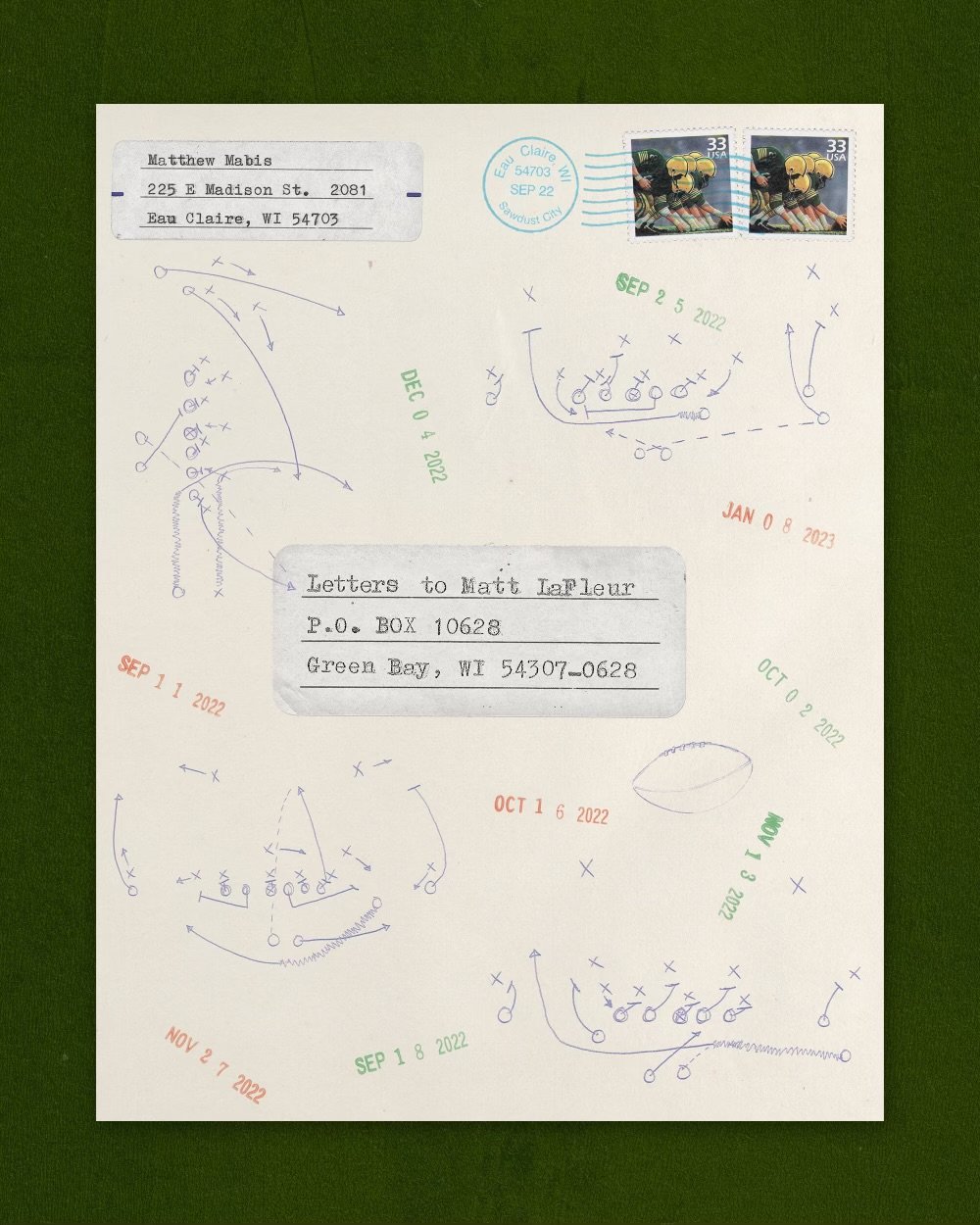

In 2022, Mabis turned toward the page. When Mabis started this project, he had no intention of publishing the letters. He only wanted to reach one person: Head Coach Matthew Patrick LaFleur. At the beginning of the 2022-2023 season, Mabis didn’t know it would be quarterback Aaron Rodgers’s last season with the Packers, after an eighteen-year stint, or that Rodgers would be out the following season after sustaining an injury on the first drive of his first game with the New York Jets. He also did not know that veteran quarterback Tom Brady would retire after twenty-three seasons in the NFL, first with the New England Patriots and then the Tampa Bay Buccaneers. Although the Packers did not make it to the Super Bowl, Mabis unintentionally captured a historic season from the perspective of a lifelong fan and former coach.

One does not need to be a football fan — or even a Green Bay Packers fan — to appreciate the letters, which starts off with an intimacy the narrator hasn’t yet earned: “Can I call you Matt? I’d like that.” Over the course of eighteen weeks, the narrator extends himself to his reader, casting out pieces of wisdom and moments of levity while wholeheartedly supporting and encouraging the recipient. Over time, we learn more about the game than we do about the narrator, but there are glimmers: the narrator’s sublime confidence, for instance, is stunning and awe-inducing, like when he tells the coach of the Packers that he has a lot to learn about competition, and asserts how he is the authority here, as the born-and-bred fan.

In week eight, we find out he’s so superstitious he’s “running out of outfits.” He writes, “Every time we lose, whatever gear I’m wearing enters retirement for the season, and the last month has sapped my wardrobe.” He blames himself for a recent loss, saying he “recycled a losing outfit” in anticipation of a blowout win. He asks, “Was this loss my fault?” And finally asks if Coach LaFleur can send his “ol’ pal Coach Mabis a little something? I need socks.”

By the time we reach Thanksgiving, twelve weeks into the season, the narrator’s aside about the turkey-heavy holiday and ensuing Black Friday sales provide another layer in this surprising portrait of a sports fan, often stereotyped as unquestioning of the country’s traditions and practices. Here is a fan who is not willing to blindly accept the status quo. Here is a narrator who believes that to love something is to question it, and to help it grow and become better. Here is a narrator who recognizes the good in others, and aims to encourage their potential.

It’s hard not to compare him to Ted Lasso, another Midwestern football coach with unflagging optimism and a deep love of the game and its players, and even his opponents.

Letters to Matt LaFleur collects the unabridged typewritten letters from 2022-2023 with Mabis’s 35mm and medium format film photographs from over the years, designed by RT Vrieze of Knorth Studios and with a foreword by author Ken Syzmanski. When I first heard Mabis talk about these letters at that bar in 2022, I immediately envisioned it as a book, and am honored he entrusted me and my company Heron Press as the publisher.

A few days after the first printing arrived, I lugged boxes of books to Milwaukee for the annual Zine Fest, hosted at the public library. Sitting behind a small table, I watched as people who didn’t know Mabis or anything about the project picked up the book, flipped it open, read a line, and started laughing. Each person who bought a copy told me a story about someone they knew who would love it. One woman mentioned her father had recently passed, and her eyes welled with tears as she told me how she was buying this for her brother so they could remember their dad. Another told me about their first time at Lambeau one winter, and the charms of bundling up beside their family and braving the cold together. Later, someone reached out and said the book reminded them of their grandfather, who sparked their love for the team.

In his essay “Calling Audibles,” Wisconsin-based author Barrett Swanson writes about how the language of football changed after 9/11, moving away from “militaristic diction” and toward “the starchy jargon of capitalism,” yet neither captured the beauty of the game. He was a quarterback in high school, and after classes, he and his father would throw wordless passes through the backyard, writing, “Somehow the trajectory of the ball authored sentiments that would have otherwise gone unexpressed between us. Every pass was a physical manifestation of the connection I hoped to establish with him but that our paucity of words chronically denied.”

To Swanson, football is a game of communication and connection. What I love about Letters to Matt LaFleur is how it’s ostensibly about football, but at its core are friends, family, and community — even the community we try or attempt to cultivate in a one-sided correspondence. (Despite multiple attempts, and unanswered voicemails to the Green Bay Packer mailroom, I cannot confirm whether there are more letter-writers out there, but it seems safe to say few are sending such detailed weekly missives from a Smith-Corona Corsair typewriter.)

Swanson points out that although altering how we talk about the sport doesn’t solve all of our societal ails, “perhaps the most potent metaphor for our national sport is one that calls attention to that rare miracle of connection between two individuals.” To walk into a local haunt on a Sunday and see Mabis and his partner, both decked in green, and seated beside Vold and his partner in their Packer gear, is to witness a profound ritual of connection and a deep and abiding love. Not just for the game or the team, but for the people on the barstools and bleachers beside us, sharing in every loss and win.

Elizabeth de Cleyre is a writer and editor. She’s the founder and editor of the longform interview series Yesterday Quarterly, the prose editor of Barstow & Grand’s issue 6 & 7, and selectively offers editorial services and communications consulting. In 2017, she helped cofound Dotters Books in Eau Claire, WI, and later founded Heron Press to publish projects like YQ and Matthew Mabis’s book Letters to Matt LaFleur. Her writing appears in Ploughshares online, The Millions, Brevity, Barstow & Grand, EAA SportAviation, and the Italian anthology Storie dal Wisconsin (Black Coffee Edizioni), among others.